“Waterpreneurs” cash in on government failure to deliver clean water to islanders

Struggle for water a daily reality for impoverished Nigerian island residents

Text by Festus Iyorah

Photos by Nengi Nelson

Data Visualizations by Yuxi Wang

It’s 2:00 pm in Sagbo Kodji, a coastal community that overlooks the Lagos Apapa seaports and high-rise buildings of Lagos Island, the commercial district of the city.

Close to a littered jetty, where dozens of wooden boats park ashore with disembarking passengers, stands Bolanle Taiwo’s wooden house.

Under the scorching sun, the single mother hunches over a green bucket of water, preparing to wash a pile of clothes before sundown. She adds a handful of detergent into the water she got from a nearby well, but it does not lather with soap because it’s “hard water” — water with a high concentration of dissolved minerals.

“The water dries the soap,” Taiwo says. “But you apply the soap again till the cloth comes to your taste [of cleanliness]. It takes a lot of soap.”

Taiwo, who sells jewellery to residents from her home, has been using hard water to do laundry, as well as to cook and clean her home, since she moved to the community in the late 1990s.

Like many of the 30,000 residents who live on Sagbo Kodji Island, she struggles to afford clean water, free of high mineral concentrations or contamination. Currently, the island has no access to potable water, and there are no public or private boreholes to compensate for it.

Less than 10% of Nigerians can access clean water from pipes in their homes.

This issue isn’t unique to Sabgo Kodji. With a population of over 200 million, access to clean water – which the UN General Assembly recognizes as a human right – is limited in Nigeria. In fact, according to 2020 water data, less than 10% of Nigerians can access clean water from pipes in their homes.

The main source of water for about 65% of the population: boreholes and tubewells, a type of well that requires a long pipe and a pumping machine to fetch water. Meanwhile, almost 60% of Nigerians say they went without enough potable water at least once in 2019.

However, what makes the plight of Sagbo Kodji residents particularly dire is the confluence of private greed and government indifference. Since residents cannot safely rely on the tap water on the island, they depend, in part, on local “waterpreneurs” who use boats to bring in tap water bought from private boreholes on the mainland.

Taiwo and her poorest neighbors remain at the mercy of both the waterpreneurs and some of the island’s existing, but dirty, wells for tap water.

Some of these waterpreneurs can be exploitative, charging far more than their fellow community members can afford for small quantities of water. But with the Nigerian government seemingly unwilling to address the island’s water crisis, Taiwo and her poorest neighbors remain at the mercy of both the waterpreneurs and some of the island’s existing, but dirty, wells for tap water.

When the residents do rely on these wells, they often get sick with water-borne illnesses, such as typhoid and diarrhoea. As painful as these illnesses can be — and as taxing as their daily water struggles are — Sagbo Kodji residents face another dire threat: government-sanctioned eviction to make space for avaricious developers who seek to exploit their desirable location.

“That’s injustice and denial of people’s right to a place they have lived for years,” says Joseph Amosu, a resident of Sagbo Kodji.

Painful toll of inadequate water access

Taiwo arrived on the island in the summer of 1999 with her mother and sister. They lived under a thatched house made from reeds, straw and palm fronds, before moving to a wooden one-room apartment with a corrugated iron roof.

While their housing circumstances have improved over the last 20 years, access to safe and clean water remains an expensive luxury.

Taiwo shares the wooden house with her daughter, mother and niece, Mariam Azeez, a trained nurse. (Her sister has since died.) Since Taiwo cannot afford potable sachets of water from local grocery stores in the community, she buys a 25-litre keg every day from the community waterpreneurs. She boils the water before using it for cooking and drinking.

Taiwo spends about 1600 NGN ($4.20) a month on these daily water purchases. That’s almost as much as some Sagbo Kodji residents pay to rent a wooden house. And it’s close to 15 percent of the daily expenditures for the more than 80 million Nigerians who live in poverty, according to a 2020 report.

Taiwo’s daily water purchases cost close to 15 percent of the daily expenditures for more than 80 million Nigerians who live in poverty.

A majority of the community is comprised of traders, artisans, vendors and boat drivers. They are part of the heavily-taxed Lagos informal economy of about 5.58 million people. According to the Nigerian Labour Statistic Collaborative Survey, in 2016, the informal sector in Nigeria contributed 9.87 trillion NGN (approximately $25.8 billion). However, paying so much in taxes leaves them with little profit to live off of.

To make matters worse, like Taiwo, other Sagbo Kodji residents complain of impurities in the community-sold water. Ocean water often seeps into the enormous tanks transporting the water in elongated motor-driven canoes across the lagoon. And when the salty ocean water mixes with the clean tap water, the locals have no way to treat it.

The waterpreneurs of Sagbo Kodji

Fifteen years ago, a group of traditional Egun men gathered at the home of one of their chiefs to discuss how to solve the island’s lack of potable water.

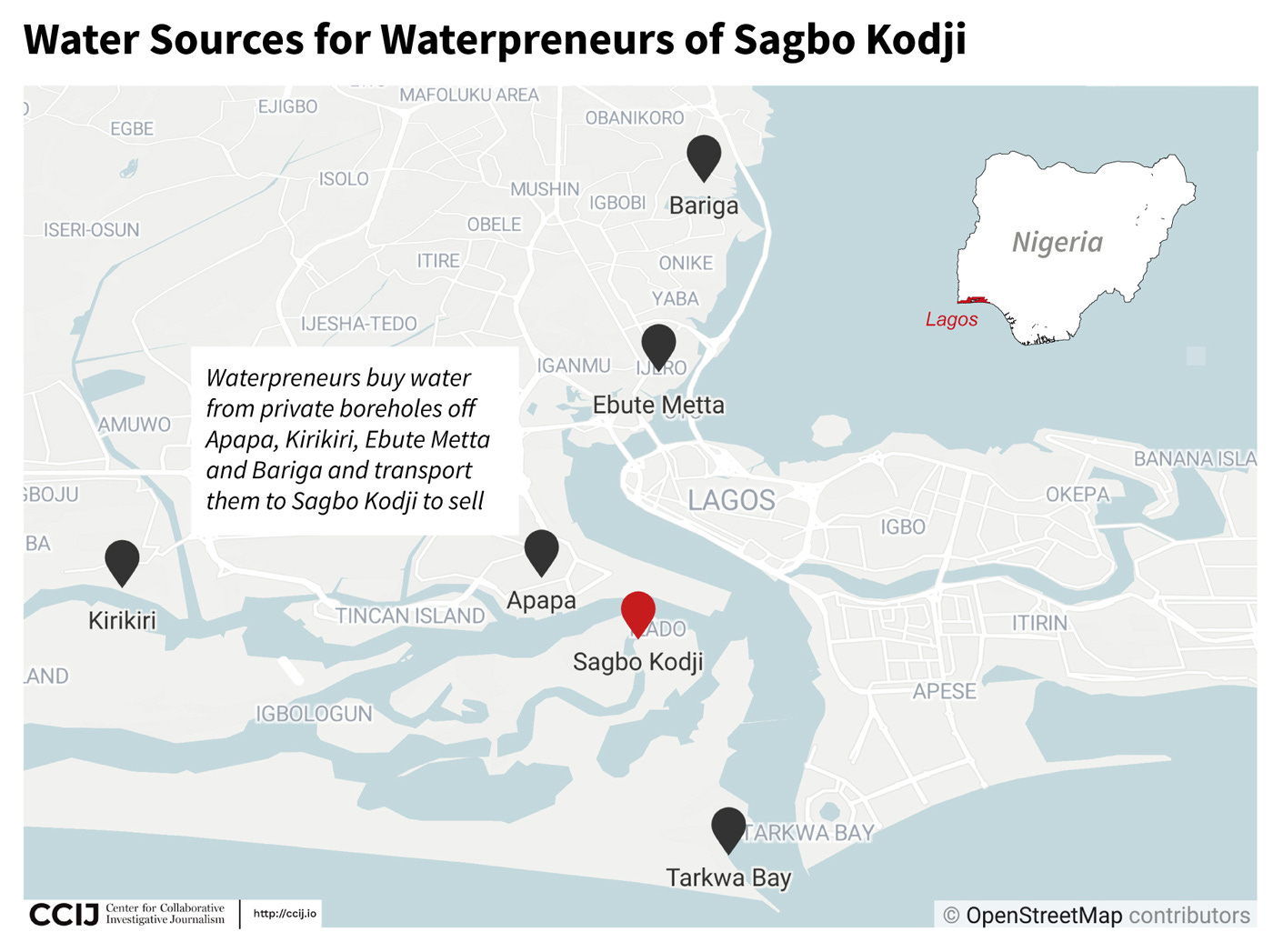

These waterpreneurs came up with a plan to supply water to residents of Sagbo Kodji using double-ended timber and fibreglass boats with motors. Every week, they make the long trip across the Lagos lagoon, braving strong ocean winds to buy water from private boreholes off the Lagos mainland areas of Apapa, Kirikiri, Ebute Metta and Bariga.

Peter Akojenu has led the business venture.

“We used to go with our boats to Kirikiri to buy water in huge tanks,” said Akojenu. “In the beginning, we sold 25 litres for 30 NGN (8 cents), but this has doubled because the cost of buying water and fuel to run our boats has increased,” explained Akojenu. He said that he spends 50,000 NGN ($131) on fuel for every trip because of “bad” engines and old boats. But another waterpreneur named John, who withheld his last name for fear of retribution, said he only spends 13,000 NGN ($34) on fuel, calling into question what the actual cost of fuel is for these trips.

The early joy at the waterpreneurs’ services has turned to hostility from some community members like Joy Aderoju, who calls them “selfish people protecting their business interests.” (Aderoju is not her real name, but we agreed to use a pseudonym, since she fears that she will be victimised for speaking out).

“A lot of people are suffering here,” she says. “Water is expensive.” She points to a brown bowl holding about 25 litres, explaining that it costs 60 NGN (18 cents).

Oluwatosin Austin, who lives with her husband and two children in Sagbo Kodji, shares Aderoju’s sentiment: “60 naira per bucket is expensive.” says Austin. “There is no money anywhere. I feel they [the waterpreneurs] are really exploiting us and they don’t care.”

A resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution, said the waterpreneurs won’t accept any — even non-governmental — water intervention projects in the community. He cited an example of when the waterpreneurs prevented a private individual from building three boreholes for charity.

“There was someone who came from Alausa (in Lagos) sometime ago,” says the resident. “They wanted to fix boreholes, but there were quarrels by the water union. They simply don’t want it. They claim it would ruin their business.”

When asked about the possibility of having the government sink boreholes with treated water to service the community, Akojenu said the government should support the water vendors rather than “take their business away” from them.

“If you build boreholes in the community for residents to drink for free, how do you expect us to feed our families and keep the business afloat?” he asked. “If the government wants to help, they should give us better boats and engines instead.”

However, if the government will not do that, Kotin, the new chairman of the waterpreneurs association who would only provide his first name, explained the one requirement for sinking a borehole in the community:

“If you want to help us, you will dig water for us and it will be under our control.. If you don’t do this, and you do it for the general Sagbo Kodji, we lose our business. And it will cause more trouble.”

“There is no money anywhere. I feel they [the waterpreneurs] are really exploiting us and they don’t care.”-Oluwatosin Austin, Sagbo Kodji resident

“If you want to help us, you will dig water for us and it will be under our control.. If you don’t do this, and you do it for the general Sagbo Kodji, we lose our business. And it will cause more trouble.”-Kotin, chairman of the waterpreneurs association

The well water hustle

It’s 6:00 am on a Sunday, and Francis Anwasu is among the first set of people to arrive at a local well. He sits in the queue, braving the cool, dry and dusty early morning Harmattan wind sweeping over the island.

Three women carrying big water bowls join him in the queue, exchanging greetings in their native Egun.

Like many on the island, Anwasu wakes up at 5:00 a.m. daily to begin the daily quest for clean water.

“I arrive here before other people,” Anwasu tells me in pidgin, Nigeria’s lingua franca that is also widely spoken across West and Central Africa. “I do this every day because this is the cleanest water in the community.”

This well is maintained by a small group of women, including Susan Abali, who contribute money every quarter to drill and renovate it. They also regularly treat the water with WaterGuard, a chemical point-of-use treatment for household drinking water, and with chlorine and aluminium sulfate.

The well opens at 6:30 am, noon and 6:00 pm, to allow people to draw water and remains open until the well is empty. It is then locked to allow it to replenish with fresh water until the next scheduled opening.

On this day, Abali unlocks the well, inviting people to collect water before it turns muddy. “People come as early as 3:00 am to drop their water bowls to fetch water,” says Abali, whose house is alongside the well. “The crowd wanting to fetch water is always massive, pushing here and there, but because today is Sunday, that’s why you don’t see them here much.”

By 6:30 am, more people arrive at the well, swarming it with plastic jugs and large water bowls. Anwasu finishes his first round of fetching after about 10 minutes, filling two buckets with water before staggering back to his home about three minutes away with a bucket in each hand.

Anwasu’s neighbour, Deborah Faton, depends on water from the well to make cornmeal porridge, a fermented cereal pudding known locally as pap, that she sells to island residents.

“If I fetch the water, I will wait for some hours to allow possible dirt and particles to settle,” she says. “Any day I don’t see colourless water, or there’s no water at all [at this well], I end up spending 600 NGN [about $1.60] on buying water that day. On days I don’t have money, I buy on credit and return the debt once I make sales.”

For Faton, buying water reduces her profit by 30 percent. So, to avoid having to buy water for cash or on credit, Faton wakes up by 3:00 am, securing a prime position at the well before anyone else arrives.

“If you get to the well quickly,” she says, “you’ll see clean water to fetch. If you don’t get there on time, you’ll get dirty water, and for me, I need clean water to survive and earn decent profits in my business.”

Well water comes with great risk

But relying on the wells has exposed the residents to frequent bouts of waterborne diseases, including typhoid, cholera and diarrhoea.

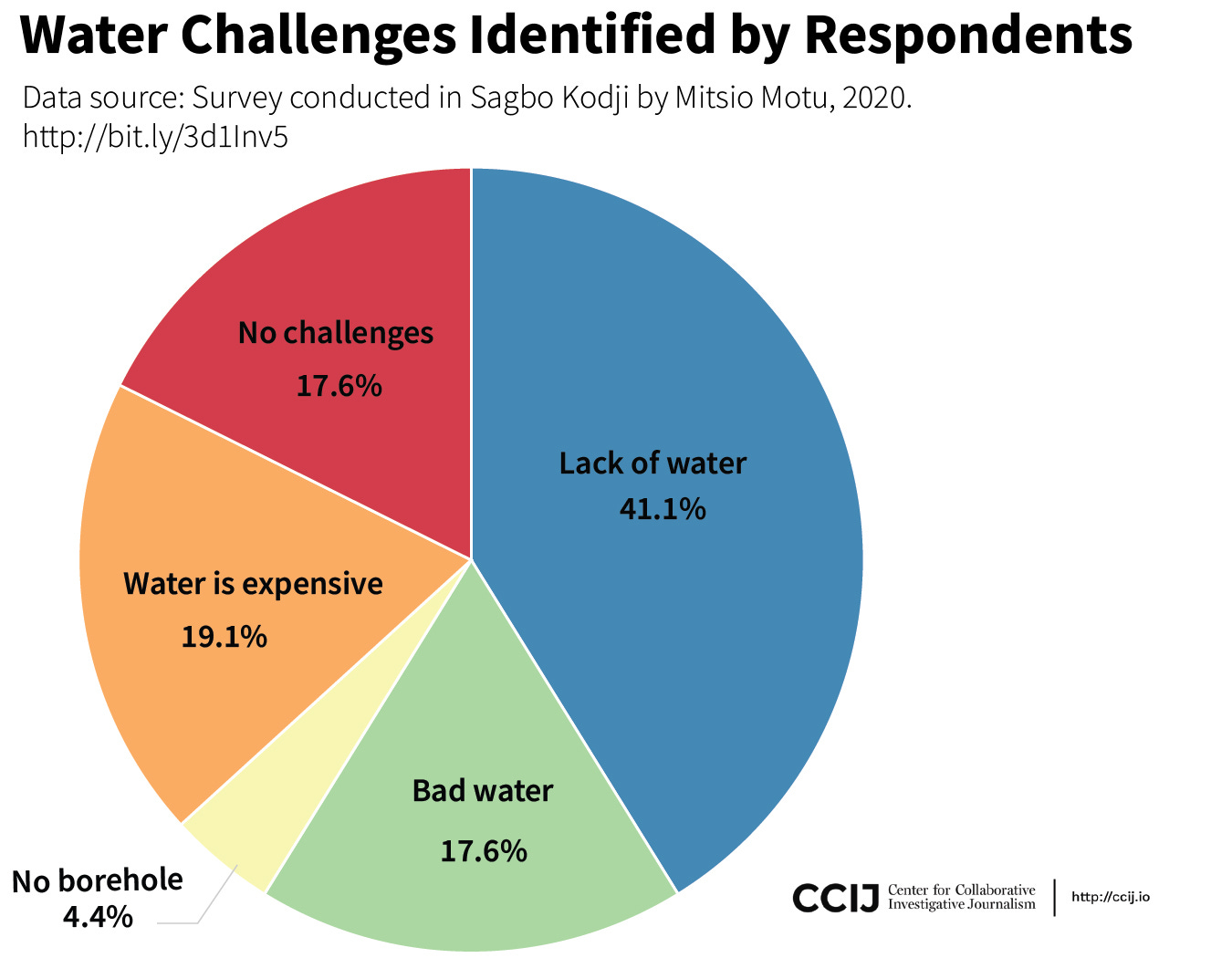

A 2020 survey conducted in Sagbo Kodji by Mitsio Motu, a consultancy working with underserved communities in Nigeria, found that 16 percent of the people they surveyed said their source of drinking water caused them to fall ill at least once a month. Respondents between the ages of 0-20 were more vulnerable to diseases like body itching, diarrhoea, rashes and typhoid.

And 26 percent of the entire survey group said their source of cooking, bathing and washing water poses health challenges, including body itching, dysentery and rashes. The water sources responsible for these problems are water vendors and shallow wells, according to the survey.

The survey results comport with the findings of the World Health Organization (WHO), which reports that cholera, diarrhoea, hepatitis A, typhoid, dysentery and polio are linked to poor sanitation and contaminated water sources.

For her part, Taiwo says she spends at least 5,000 NGN ($13) treating typhoid every three months, which is how frequently she contracts the illness. Fortunately, her niece, Azeez, the de facto family nurse, treats Taiwo and the family at no additional cost.

“I give drips [of intravenous fluids] to wash the system once and for all; I also write drugs to treat water related issues such as typhoid… I do the service for free,” Azeez explains.

Treating the sick

Sagbo Kodji has only one health centre with limited access to drugs and health workers. When a doctor does visit — which is usually once a week — large numbers of people converge and wait in line for hours to be seen.

As such, community nurses like Azeez play a critical role day-to-day. In addition to treating her aunt and grandmother, Azeez spends her time treating other residents for a small fee.

Azeez starts every diagnosis with taking patients’ blood — to be sent to a laboratory off the island for tests on the mainland. Once test results are in, she prescribes drugs that treat any ailments from cholera to typhoid, following up with phone calls or home visits to check progress.

Blessing Osagie is one of her patients. The mother of five spends 600 NGN ($1.60) every three days buying pure water from the groceries stores in the community and another 640 NGN ($1.68) every three days on tap water she buys from the waterpreneurs for cleaning and cooking.

Osagie has purchased water since contracting skin rashes after drinking well water. Still, despite her best efforts, she gets sick from time to time – including from malaria, a mosquito-borne illness which is also prevalent in the community.

“The water situation here is very bad…that’s why there are mosquitos everywhere,” says Osagie. “The mosquitos are mostly from rivers and drainage, and malaria has been my normal sickness.”

Community nurses like Azeez play a critical role day-to-day. In addition to treating her aunt and grandmother, Azeez spends her time treating other residents for a small fee.

Evicting the poor to make way for the rich

Sagbo Kodji’s water crisis is as old as the community, yet the island’s lack of access to potable water does not appear to be the government’s concern. In its quest to remodel Lagos — and its many islands — into a megacity, the state government appears to consider Sagbo Kodji’s community an impediment to converting the island into a real estate development opportunity and chance for urban renewal. (The state government declined to respond to calls or texts about this characterization.)

In the last five years, coastal communities with problems that mirror Sagbo Kodji’s reality have been uprooted with impunity.

Residents in at least two dozen slums, waterfront communities and islands like Sagbo Kodji have faced eviction at the hands of the Lagos state government officials, according to Justice and Empowerment Initiatives (JEI), an organization working with informal communities.

The latest Lagos state eviction targeted Sagbo Kodji’s neighbour, Tarkwa Bay, known for its beautiful beaches that attract large numbers of visitors. Like Sagbo Kodji, many of the residents at Tarkwa Bay are low-income earners who can’t afford rent on the mainland.

When Tarkwa Bay dwellers and other coastal communities got wind of the impending eviction, they filed a suit at the Federal High Court in Lagos. They restrained the government from carrying out evictions in the community — at least temporarily.

But the Lagos state government disobeyed the court orders. On January 21, 2020, gun-wielding navy officers stormed Tarkwa Bay to evict impoverished residents living on the island.

Abali, one of the water guardians in Sagbo Kodji, was one of the 4,500 people evicted from Tarkwa Bay last year. And like every other resident here, she says her fear of eviction is stronger than the quest for potable water.

The Lagos state government says the latest round of evictions were aimed at tackling oil theft operations along pipelines that run through the slum and has denied any wrongdoing. However, other than releasing a statement alleging oil theft and mentioning the existence of a report we could not find to substantiate the allegation, the government has shown little evidence of oil theft.

Civil rights groups and analysts, such as JEI and Nigerian Informal Settlement Federation, say the Lagos state government’s claim is a cover-up for its real intention — to turn the island into luxury real estate properties, which it has done on neighboring islands already.

Meanwhile, the Nigeria Navy, which evicted islanders at Tarkwa Bay, said they had received an order from the government to tackle insecurity on the islands through forced evictions.

The evicted and threatened communities — with the help of JEI — are currently in court to challenge the violation of their fundamental human rights, but suspension of court sittings due to the COVID-19 pandemic has stalled proceedings.

Back in Sagbo Kodji, an unshakable premonition of eviction pervades the community.

Islanders like Azeez, the community nurse, express disappointment over the government’s failure to provide basic social amenities like running water and electricity and its effort to displace people from the community.

The waterpreneurs’ desire to extract all they can from community members while blocking access to free water does not surprise her.

“I don’t blame them [the waterpreneurs] because they’re copying the same government who are oppressors and believe they own the lands and can chase us out anytime,” explains Azeez.

Although she might be able to stay at her aunt’s mainland home should an eviction take place, she worries about the islanders who don’t have a similar option: “My only concern is with people who are most vulnerable and can’t afford to get a house on the mainland. If the government chases us away, where would they go to?”

This report, first published on the CCIJ website, was produced in collaboration with the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), supported by Wits Journalism and Civicus.