Making Special Drawing Rights Truly “Special”

Have you ever heard of a story, where you were left wondering if you were awake or having a bad dream?

Have you ever heard of a story, where you were left wondering if you were awake or having a bad dream?

I have witnessed many cases of lack in different African countries, but some have stuck in my mind. One of them is of a 36-year-old widow Peninah Kitsaho, who was left with 8 children when her husband passed away, and she would cook for them stones with the hope that they would wait for so long for “food” to get ready and they would hopefully fall asleep while waiting.

It is usually disturbing to listen to such stories of people hopelessly narrating how the pandemic has negatively affected them to a point of struggling to afford most of their basic needs such as food, shelter and water without mentioning healthcare which was extremely crucial during the pandemic.

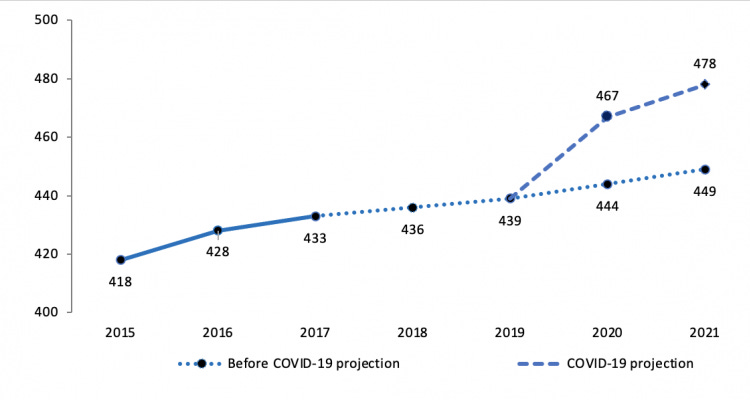

The economic and social disruption has been devastating as tens of millions of people have found themselves faced with the risk of falling into extreme poverty. Focusing on Africa, the number of extremely poor in the region increased in the last two decades, to an estimated 439 million in 2019, which was more than two-thirds of the world’s extremely poor.

Even though the number of poor was already projected to increase in 2020 and 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed an additional close to 30 million people into extreme poverty. There have been losses of lives and jobs both formal and informal and the hunger crisis which was caused by the unexpected loss of income for countless millions who were already living hand-to-mouth. Moreover, there was the collapse in oil prices; shortages of hard currency due to lack of tourism; overseas workers not having earnings to send to their families in Africa and problems like climate change and other humanitarian disasters that were going on even before the pandemic and they did not stop during the same period.

Trying out Potential Solutions

Besides Debt Service Suspension Initiative and other stimulus packages to economically support countries during the pandemic, various Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) requested the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to release Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) amounting to 2Trillion in SDRs which is equivalent to USD 3Trillion.

The biggest reason for the SDRs demand was because the issuance was regarded as one of the viable options to support economic recovery for countries that were in a tight financial position caused by the alarming level of debt they shoulder and the economic decline which got worsened by the Covid 19 outbreak.

SDRs were not meant to solve all problems linked to pandemics, unsustainable debt and ensuing economic struggles, but they were expected to go a long way in supporting immediate economic recovery for most needy nations. The IMF came through and released $650 billion worth of SDRs.

Issuance and Allocation of SDRs

Though the issuance of SDRs was good news since they rarely get released, IMF rules usually cause SDRs to be allocated to countries based on the relative size of their economies, not their actual need to respond to a certain crisis. This arrangement is neither equal nor very helpful because for example, only about U$275 billion went to emerging and developing countries and low-income countries only received U$21 billion. Mind you, the UK, as one of the IMF’s largest members, received roughly $27.5 billion worth of SDRs, more than all low-income countries combined. A case of annoying inequality, right?

This is so ironic since the aim of the allocation, according to IMF, was to “help most vulnerable countries struggling to cope with the impact of the COVID-19 crisis”. Now having the largest chunk of the SDRs sitting idle on the balance sheets of high-income economies is awkward. So basically, and as you already notice, there are major issues with the IMF's way of doing certain things:

· The allocation was determined by what is politically feasible rather than actual needs. Therefore, the distribution of SDRs reproduces the inequalities of the global financial system: they are allocated in proportion to IMF members’ quotas, meaning that they favour rich countries.

· Allocating the highest amount to rich countries and giving poor ones what looks like leftovers, hardly makes any sense since it will not bring many rescues to either rich countries (who don’t need SDRs but have plenty of them) or poor countries (that need them but only have a meagre portion of the same). Picture someone overfeeding to a point of getting sick, yet there is a starving individual right next. It may sound ridiculous like “who does that”? But it happens, and this SDRs allocation is a very good confirmation that it does.

You see, for most indebted countries, the amount of SDRs received was less than the cost of their debt service in 2021. Therefore, some countries, especially those who were struggling to repay their loans, only used allocated SDRs towards loan repayment. In other instances, those funds were used to reduce their budget deficits or support their Covid 19 responses while others either boosted their reserves or paid for imports. So yes, SDRs provided some fiscal relief but they got finished too fast.

Therefore, one can safely say that IMF did not achieve the outcome of really promoting economic recovery. As a disclaimer though, the SDRs issuance was not a useless act, it was helpful but to a limited extent. That’s why there must be a different approach that the IMF can use going forward, to support the most vulnerable countries as per its stated intention when issuing SDRs.

Making Special Drawing Rights really “Special” for people

· The international community needs to build an effective SDRs reallocation mechanism. Actually, in recognition of this problem, the G-20 has charged IMF with advancing options for recycling SDRs to those countries that need them most.

· At least 75% of the UK’s SDR allocation is re-channelled towards needy countries.

· While the creation of $650 billion in SDRs is unprecedented, it is not enough. The United Nations has estimated emerging markets and Low & Middle-Income countries (MICs) actually require upward of $2.5 trillion to restore liquidity and gain the fiscal space for a proper recovery.

· Indeed, the allocation would only be effective and impactful if there was a commitment to reform the global debt architecture and create a fairer debt-creditor relationship.” Jason Braganza, Executive Director- African Forum and Network on Debt & Development (AFRODAD).

· SDRs should be used as effectively as possible, with accountability and transparency because governments should responsibly use all finances entrusted to them; this is in line with the Harare Declaration

· Wealthier countries are urged to reallocate their SDRs in a non-conditional way in addition to existing commitments to benefit people who are struggling under the lingering socio-economic negative effects of the pandemic. Indeed, the IMF should explore options for members to channel SDRs on a voluntary basis to the benefit of vulnerable countries.

· SDR channelling should be used to provide debt-free financing to countries, to avoid worsening the problem of unsustainable debt burdens of developing countries,

· SDRs issuance is not just an exercise, it must be perceived as a rescue act for many who desperately need them. They must be sufficient, and they should get fairly channelled to those who need them most. It’s only then that Special Drawing Rights will become truly “Special” for vulnerable people like Peninah, women, people with physical or mental challenges, the youth and the elderly.