John Chilembwe's Legacy: Unraveling the Philosophy Behind the 1915 Uprising

As Malawians gather on this anniversary, Chilembwe's call for a “resurrection” unfortunately remains largely unrealized in a nation still struggling with many of the same injustices he fought against.

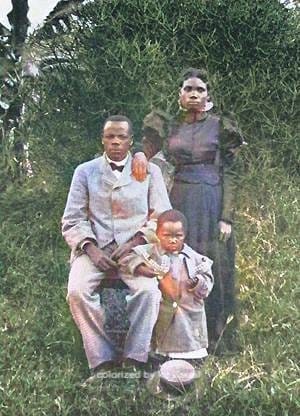

LILONGWE, Malawi — As Malawians on Monday marked the 109th anniversary of the Rev. John Chilembwe's 1915 uprising against colonial rule, debate continued over the underpinnings of his long unrealized call for a “resurrection” to liberate natives from European domination, writes Justin Mthawanji.

“The first resurrection is the freedom from bondage and slavery and the second resurrection is when the African poor and exploited would come into their own and create a just society,” Chilembwe preached, according to author Rester Halecheni Chopi's writings.

The Baptist pastor and educator railed against the unjust treatment of Africans under British rule in Nyasaland, now Malawi.

He channeled his outrage into a liberation theology that would inspire Africa's first anti-colonial revolt.

According to scholar Barry Rubin, who studied revolutions and insurrections, no rebellion can occur without an animating philosophy.

Chilembwe's “resurrection” ideology filled that role.

He first tried peaceful means. In 1895 he founded the African Christian Union of Nyasaland alongside Joseph Booth to advocate for equal rights.

After the group failed to take hold, Chilembwe worked to uplift the native community by opening schools and preaching self-improvement.

But the white settler community resisted his efforts.

Chilembwe appealed to the colonial authorities in a series of letters detailing the cruel exploitation of tenant farmers on European-owned estates.

But his pleas went unanswered. By 1915, he decided only direct action could free his people.

On Jan. 15, armed supporters of Chilembwe attacked white settlers, killing three. The uprising was swiftly suppressed by colonial forces, and Chilembwe was shot dead a few days later while fleeing.

A century later, debate continues on whether Chilembwe was ahead of his time. The North Nyasa Native Association damned the revolt in 1919 as “a black mark,” arguing Africans were better off under European control — a view some Malawians still hold.

“Chilembwe was in a hurry to improve the welfare of the natives who couldn’t understand his philosophy till modern day,” said John Mtitima, an African history scholar.

As Malawians gather on this anniversary, Chilembwe's call for a “resurrection” unfortunately remains largely unrealized in a nation still struggling with many of the same injustices he fought against.