From Struggle to Prosperity: Hope Water Project Transforms Lives at Dowa Turn-off

Women, who make up the majority of the project's customers, no longer spend their days waiting in line for unreliable boreholes.

DOWA, Malawi—In Malawi, where millions of people still lack access to safe water, the Hope Water project is transforming lives at the bustling Dowa Turn-off trading centre, providing clean water and unlocking a once-impossible future for residents, writes Winston Mwale.

"Before, our days revolved around the struggle for water," recalls Meclina Hazwell, a local resident.

"Now, we're building businesses, improving our farms, and watching our children thrive."

This sentiment echoes through the community, where the simple act of turning on a tap has become a symbol of progress and possibility.

Initiated in 2021 by the Rhema Institute for Development (RHID) with support from Hope for a Child, the project has rapidly grown to serve over 1,500 households.

But beyond the numbers lies a story of resilience, innovation, and the profound impact of accessible clean water on human potential.

"People were drawing water from the boreholes. They would go in the morning and they would come back in the afternoon and sometimes in the evening," recalls Alinafe Chapotera, a project officer with Hope Water.

"It was hindering them from achieving their daily goals and activities."

The project, which began operations in 2021, has grown rapidly.

Chisomo Chawiya, the sales and marketing officer for Hope Water, reports that they now serve about 1,500 customers through water kiosks and an additional 175 through prepaid home connections.

"At first we had 1,000 customers," Chawiya says. "Now, they say there is a lot of ease."

The system operates on an innovative model.

Kiosk users purchase tokens, which they can then use to collect water at designated points.

Those with home connections buy water units and enter the codes at home to access water.

The pricing is designed to be affordable: K2,500 for 1 cubic metre of prepaid water, or K250 per 100 litres at the kiosks.

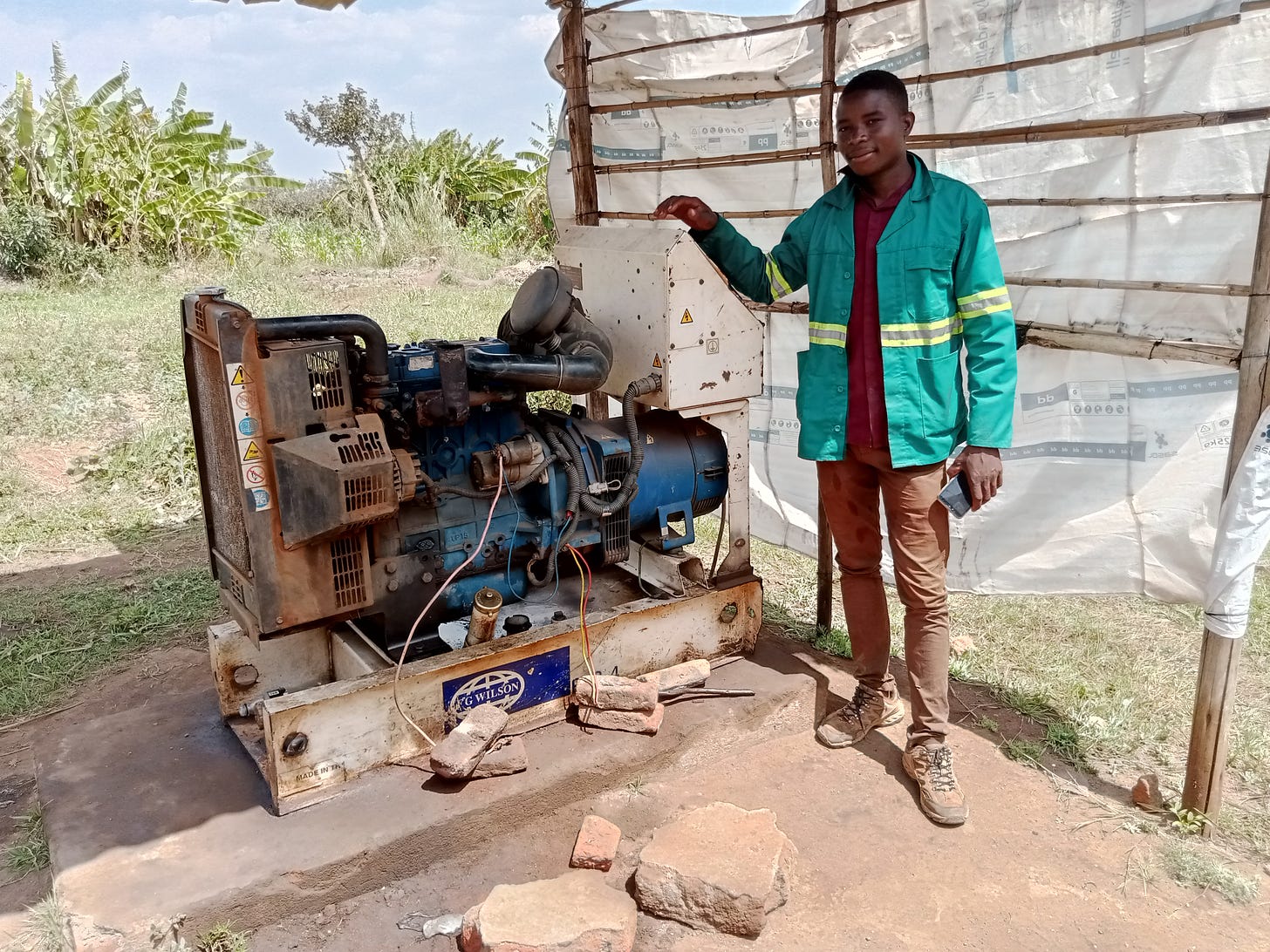

However, the journey hasn't been without challenges. Initially, the project used solar power to pump water, but inconsistent sunlight led to supply issues.

They've since switched to diesel pumps, which, while more reliable, have increased operational costs.

"It's very expensive because we actually use diesel to pump the water to go to the tanks and then to the pipes," Chapotera explains.

To manage costs, they currently pump water once a day, though they acknowledge this isn't ideal and are planning to expand their capacity.

The project has also faced some resistance and misunderstandings from the community.

"When we visited, it was very tough because they thought it was going to be cheap—not cheap as such, but it was going to be free," Chapotera says.

"They didn't know that we were going to put a price on top of it."

Chawiya adds that some customers struggle to understand their water usage.

"You find a customer buying one cubic meter, that's like 1,000 litres of water. And they expect to use that amount of water for about a month," he explains.

"And that's not possible to use, like 2,500 kwaja for a month."

Despite these challenges, the impact on the community has been significant. "The water project has improved people's lives in the sense that people are now getting clean water," Chapotera says.

"I can say clean water because of the boreholes they were using, some were complaining of infections and things like that."

The project has also created employment opportunities.

Falison Andrew, a plumber with Hope Water, shares his experience: "As a plumber, I have benefitted because before I started work here, I had difficulties feeding. Even finding accommodation for me and my family was a problem."

Andrew's role involves connecting pipes, installing prepaid meters, and monitoring water usage.

He also faces the ongoing challenge of vandalism.

"There are some people who vandalize water pipes and taps at the kiosks," he says.

"In mitigation, we sit down with the people and remind them of the importance of this water."

The Hope Water project aligns with broader development goals for the region.

According to RHID, it "constitutes a timely complementary effort... to the implementation of Dowa District Council plans aimed at ensuring that all the fast-growing trading centres in the district migrate from borehole technology to piped water supply technologies."

Looking to the future, both Hope Water and RHID have ambitious plans. "We plan that we want to go to other districts," Chapotera says, mentioning Madisi as a potential next location.

Chawiya echoes this sentiment: "It's a very good project, and I would love to see it go in some other training centres."

As the sun sets over Dowa Turn-off, the impact of the Hope Water project is clear.

Women, who make up the majority of the project's customers, no longer spend their days waiting in line for unreliable boreholes.

Families have access to clean water, reducing the risk of waterborne diseases. And for some, like Andrew, the project has provided not just water, but a livelihood.

In a region where access to clean water can mean the difference between poverty and prosperity, health and illness, the Hope Water project is proving that with innovation, community engagement, and perseverance, positive change is possible.

Innocent Semu, Executive Director of the Rhema Institute for Development, highlighted the struggles residents endured, often spending excessive time fetching water from unreliable sources and sharing this vital resource with livestock.

“Water scarcity has been a major barrier to progress in our community,” Semu stated.

“Families were forced to share water with cows, goats, and dogs, impacting their health and hygiene.”

In response to these challenges, the Rhema Institute launched the Hope Water project, aimed at improving access to clean water.

The initiative has led to transformative changes within the community.

Residents can now focus on their businesses and personal development, and children are attending school regularly, an opportunity that was previously jeopardized by the time spent sourcing water.

Semu noted that the project has also fostered better community relations.

“Before the project, women often found themselves in disputes while queuing for water at unreliable sources,” he explained.

“Now, they can access water at their convenience, allowing them to plan better and pursue their personal goals.”

The Hope Water project has not only addressed immediate water needs but has also significantly improved the quality of life for residents in Dowa Turn Off.

As the community continues to thrive, the initiative stands as a testament to the impact of sustainable development efforts.

Overall, the success of the Hope Water project highlights the importance of addressing basic needs to foster both individual and community growth in Dowa Turn Off.