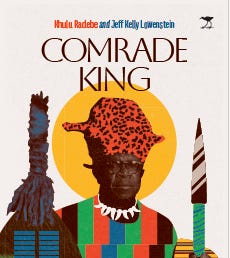

Excerpt from Comrade King by Khulu Radebe and Jeff Kelly Lowenstein: Violence in Alexandra

A chain of shacks stood close to our house. Most of the occupants were Xhosa people, and the hostel dwellers started by murdering them.

INTRODUCTION: After the initial flush of joy at returning home from exile, Khulu Radebe and other residents of Alexandra Township endured an unprecedented suffocating feeling during the period in the early 90s that came from the police establishing a razor-wire barrier around the township that locked everyone inside it. Often called ‘black on black violence’, the murders were the product of the reigning National Party being in cahoots with the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). He and his new wife Margaret witnessed many searing incidents of violence and nearly were killed themselves during this time.

TEXT: In Alex, the violence started on a beautiful Saturday morning, when men were bused in from different hostels outside the township into Alexandra stadium. You could see many buses and taxis coming into the stadium and making it their assembly point. The Afrikaner

police drove into the stadium with an arms cache in a white kombi. The taxis and the hostel dwellers started spreading out and killing people shortly after that.

We knew that this type of violence had already started in Natal. They wanted to get rid of all of the Xhosas and so get rid of the ANC. ‘We don’t have any problem with any Zulus, but we want

to get rid of the Xhosas because they are ANC.’ That’s what these guys had been told. That was when we’d realised that the National Party and De Klerk were in cahoots with the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

My friend Keiko, who was from Japan, had slept over the night before and ended up witnessing one or two of the killings that ensued. I knew that we had to get her out of Alex as soon as I sawthe men gathering at the stadium. Even though I didn’t own a car to move her, I knew that Keiko had to go.

My wife and I had to handle this situation. If we had to die, we had to die, we decided. In addition to Keiko being our friend, there would be an outcry from Japan if she was killed. I eventually managed to arrange for her to stay with Andrew Mlangeni, the Rivonia Trial defendant.

A chain of shacks stood close to our house. Most of the occupants were Xhosa people, and the hostel dwellers started by murdering them. We saw it happening. They shot people. They even shot one of their own. There was blood everywhere. They mostly killed men, but murdered women, too.

At various times that day a taxi came into Alex, pretending to be taking people to town and moving around the township looking for customers. Once the taxi was packed, it was driven to the hostel. Everyone was killed, even children. The driver was one of the killers.

They killed a woman with a baby on her back on the stoep of my wife’s house. The baby survived the attack, but was left screaming on top of her dead mother. They also murdered a man who was approaching the house. My wife had to hide and keep silent because they would have come for her if the man had seen her and called for help. To this day, she does not want to go to that part of the community. She is too traumatised by the memories of what she saw

and heard.

These developments were not totally surprising to me. When we’d travelled to Japan with Amandla, we’d seen a group of young people from Natal who were on their way to Israel for military training. This was during the time when South Africa and Israel had a close connection. We’d met them at the airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and had learned what they were going to be doing in Israel while chatting to them in isiZulu. We started engaging with their leader, who was not forthcoming. We overheard him shouting harshly at the youths for the mistake they had made in sharing that information with us.

I suspected that these same young boys were among those being dispatched to hostels to target Xhosa-speaking people.

Many of the original hostel dwellers in Alex were amaPedi people from Limpopo and amaBhaca people with their roots in the Eastern Cape. They worked for the Sandton Town Council and a milkprocessing plant close by. There were also some Masinga from the abaThembu clan in the region of Msinga in KwaZulu-Natal, whose adults pierced their earlobes and wore ornamental earplugs. They never joined in the killings as they do not consider themselves to be part of the Zulu nation or the Zulu Kingdom. In other words, the lawful occupants of the hostel did not include any Zulus.

On that Saturday morning, these rightful hostel dwellers had to relocate while the killers moved in.

The police threw up a razor-wire barrier around Alex that had the effect of locking everyone inside with the IFP. We watched events unfold through the window.

The attackers had information about who among the community supported the ANC. People had joined the Congress in big numbers after its unbanning in 1990. By then, my wife was a well-known office-bearer with the ANC Women’s League.

When my wife ventured out of the house she encountered groups of Zulu people from Alex marching along and chanting warrior songs. Some of them would greet her quietly so that no one should be aware that they knew her. ‘We are not in Inkatha, but we are forced by the conditions to take part in these marches,’ they would tell her.

It was clear that conflict had been imported into Alex. Many people were bused into Alexandra and dropped off at the stadium.

They used to sleep there, then go out to kill people in the township. The Inkatha leaders and members, who had commandeered semipermanent space in the Madala Hostel by kicking out most of the traditional amaPedi and amaBhaca occupants, were also involved in the killings.

Being encircled by the enemy was suffocating. You felt as if you couldn’t breathe properly the whole time. You couldn’t say, ‘Let’s run away.’ The Afrikaner police stood on the other side of the fence, and the only time they would open it was to bring in more arms for Inkatha. It was a situation of basic survival.

I had come home to a war zone that was more tense than growing up under apartheid, serving time on Robben Island, or surviving in Angola. We slept and ate in the same area as the killers. It was so bad that people named the area ‘Beirut’.

We eventually came to a clearer understanding of what was happening. Even though the term ‘black-on-black violence’ was used to describe the situation, the true origin of the murders was that the racist regime in South Africa had found parties through which to perpetuate its ideology and carry out its objectives. When you analyse it from a Marxist-Leninist perspective, you need to think of the form and the content. The form was the violence between Zulus and Xhosas, while the content was that the number of people who were likely to vote for the ANC needed to be reduced.

Excerpt from Comrade King by Khulu Radebe and Jeff Kelly Lowenstein, all rights reserved. Comrade King is published by Jacana Media. The launch event will be streamed live on Tuesday, August 15 at 1800 SAST. The e-book can be purchased by going to: https://rb.gy/aa5hl.