Communities turned into sewage swamps

South Africa’s waste water crisis is making life unbearable for its residents

By Steve Kretzmann

Photos by Steve Kretzmann

Data visualizations by Yuxi Wang

Johan Lotter and his parents moved into numbers 2 and 2A Johann Street in Standerton 15 years ago, planning to spend the rest of their lives there.

Located in a cul-de-sac on the banks of the Vaal River, it seemed ideal for Johan, who had taken an early retirement after the family plumbing business down-sized. He had planned to look after his aging parents and spend more time enjoying two of his favorite hobbies, gardening and baking, in between lecturing at a local technical college. But for the past three years gardening has been out of the question, and baking is much less appetizing, as both properties have been flooded with sewage.

The houses sit on the lowest residential portion of land in Standerton’s Meyerville area, where sewer line blockages and pump station failures have caused waste to back up and overflow, turning the properties into a permanent garbage swamp.

Johan said the sewer line started to get blocked on a regular basis from 2009. It gradually became more frequent until the overflow became permanent in late 2018, with sewage engulfing their yards.

Making matters worse, the permanent saturation of the ground has caused the building’s foundations to give way. Johan pointed out new cracks in the walls and rising damp that has led to black mold forming inside.

“I’ve developed asthma and am getting headaches because of the continual moisture in my room,” he said, now forced to share one house with his parents.

Living in a “garbage heap”

It’s a familiar story. Tulani Habile lives in the third house in the cul-de-sac. He shares it with his mother, sister, aunt, his 13-year-old son and nine-year-old daughter. Although his house is on slightly higher ground, the town’s sewerage failure means his own drains are permanently blocked, resulting in all the household wastewater flowing into the yard.

Habile also pointed to new cracks in the walls where the drain is situated – a relic of the continual damp – not to mention the stench from the sewage swamp that permeates the air. Beyond the obvious health impacts, Johan explained how living in sewage is “depressing,” and Habile says his children are teased at school for their living conditions.

“My daughter gets teased at school. Even friends she used to play with, they say ‘you’re staying in a garbage heap,’ and laugh at her. Her friends don’t visit anymore.”

He said it’s the same with his son, whose friends no longer come over to play soccer.

Litigation by the Freedom Front Plus (FF+), a conservative political party, has been brought against the Lekwa Local Municipality within which Standerton falls, seeking compensation on behalf of the Lotter and Habile families, but so far, nothing has come of it.

The entire town’s sewerage system is failing

While the Lotters and Habile’s houses may be the most visibly affected, the entire town’s sewerage network is failing.

A two-and-a-half hour tour across Standerton with municipal councilor Wilma Venter revealed sewage spill after sewage spill. There was not a single manhole or pump station that, if not currently overflowing, didn’t show evidence of substantial recent overflows. All of which severely pollutes the streams and wetlands which drain into the Vaal River flowing through the town. Venter pointed to marshes that used to be playgrounds for children, but are now cesspools.

At a pump station on Taljaard Street the security guard used stepping stones to cross a pond of sewage between her guard hut and the boundary gate. Although the pump station was working at the time, she said it is switched off from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m. every day. During those 15 hours, the sewage it is designed to pump to the wastewater treatment plant, simply overflows into the yard and across the street. She said she did not know why it was switched off. Venter also didn’t know why. A further request seeking comment from the station was ignored.

Venter, who was elected ward councilor for the area during the municipal elections in November last year, had previously been a community activist, continually reporting sewerage failures to the municipality and pushing for action for five years prior. She showed this reporter house after house marked by years of sewage spills. Behind an apartment block on Berg Street, she pointed to an open field that she said usually has a fountain of sewage spewing from it.

At the time of our visit the water pressure was reduced due to maintenance work being conducted on the town’s water purification pumps, but Venter said it had been overflowing for ten years. It was evident that entire lines were blocked or collapsed, sewage was spilling out of every manhole; across streets, into gardens, and into the Vaal River. Questions sent to the municipality as to why their sewerage network was dysfunctional were ignored.

But this report is not just about Lekwa municipality’s sewerage network failing – as it clearly is. Data from the entire region’s municipal wastewater plants show a pattern of toothless oversight and fiscal mismanagement, not only failing the people who live there, but potentially affecting more than 13 million people who rely on the Vaal Dam for their drinking water. It also offers a dire warning if no action is taken to rectify it.

Toxic water

According to the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) Green Drop Report for 2022 – an audit of all wastewater treatment works in the country for the period July 2020 to June 2021 – Standerton wastewater treatment works is 164% over capacity, achieving an overall score of just 17%, which puts it into the ‘critical risk category.’ No data on the quality of its effluent, which is released almost directly into the Vaal River, was loaded onto the DWS online regulatory system, which it is mandated to do on a monthly basis, during the first quarter of 2022.

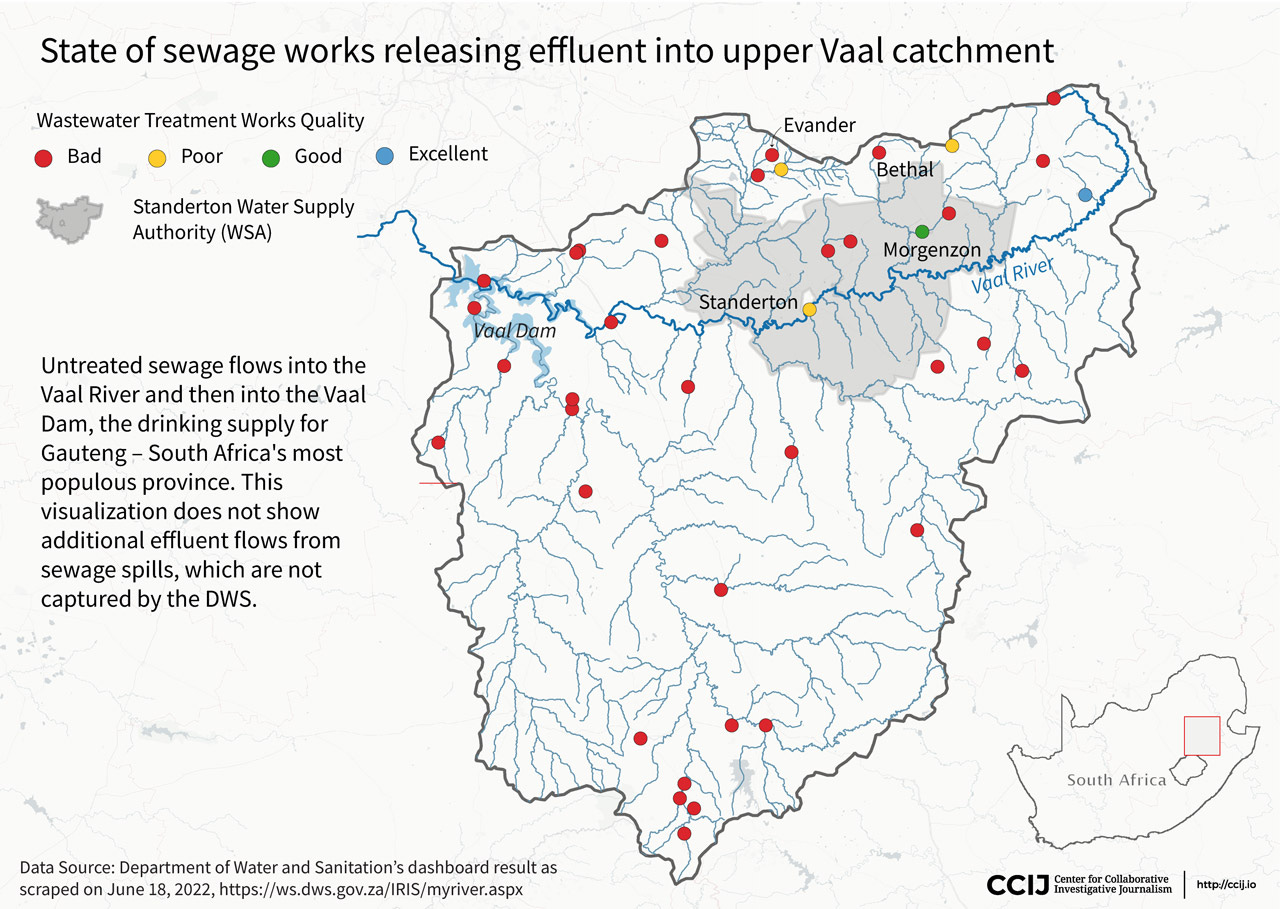

A visit to the plant revealed untreated sewage spilling into the environment from just outside the perimeter fence, and flowing into the Vaal River a stone’s throw away. From there it flows into the Vaal Dam, the drinking supply for Gauteng – South Africa’s most populous province, including the economic hub of Johannesburg and the capital city, Pretoria.

The failure within Lekwa municipality is not confined to wastewater and pollution of the Vaal. The drinking water supplied by the municipality, which is extracted from the Vaal, is not drinkable.

The water from the taps “smells like ammonia” and is brown, said Lauren Nienaber who lives at the bottom of Coligny Street with her husband Andre.

Andre revealed a small reverse osmosis system underneath the kitchen sink which they use to purify the water from their tap.

He said they have to change the filters every three months, costing R500 ($29), as well as a “main filter,” which costs R800 ($47). This is above what they have to pay the municipality for water use and supply.

“We don’t even cook with the tap water,” he said, it all goes through the purifier first.

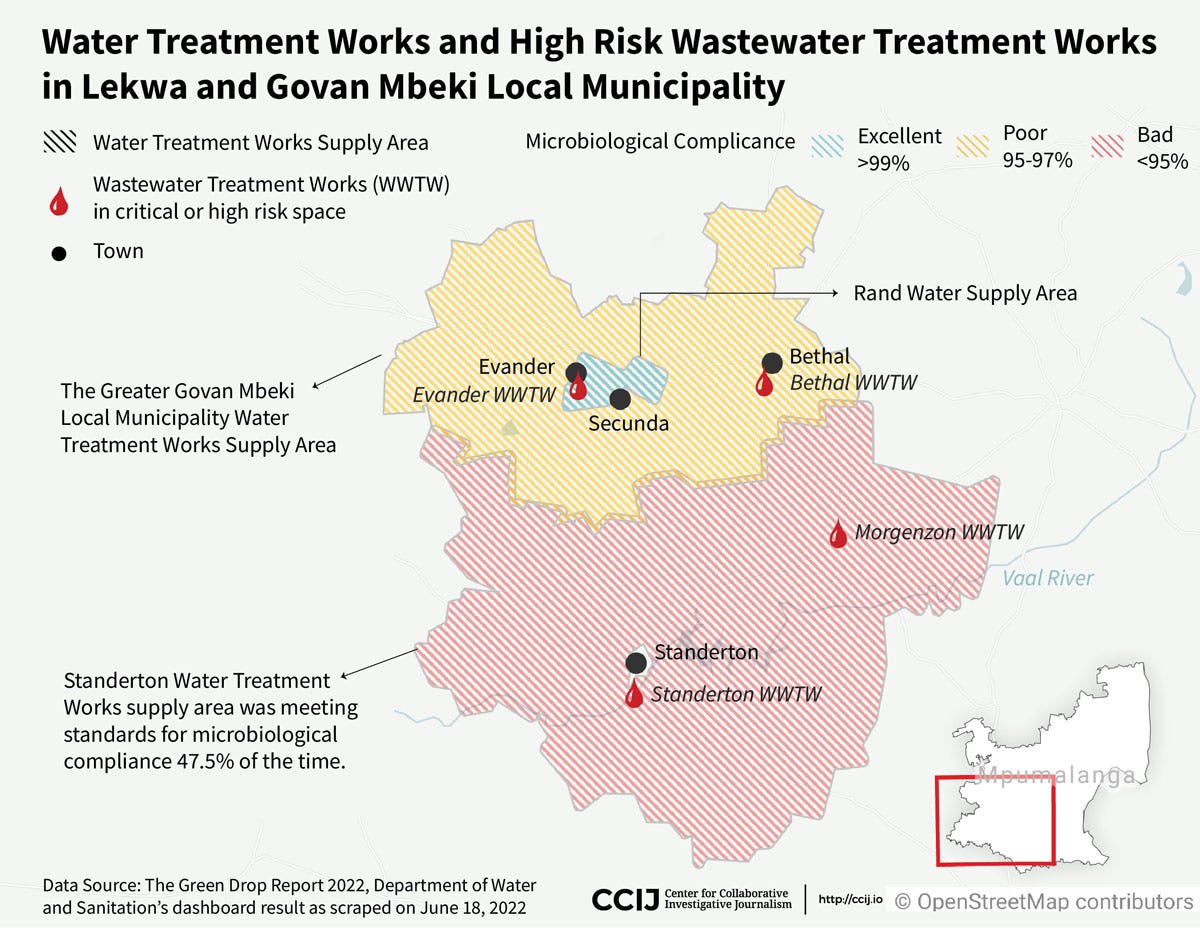

Their perception is backed up by data on the DWS system. Figures from June 18 show Standerton Water Treatment Works (WTW), which is run by Lekwa municipality, was meeting standards for microbiological compliance (fecal coliforms such as E.coli and enterococcus) just 47.5% of the time. The figure for chemical compliance was 0%. Both these indicators, among others, are supposed to meet the South African National Standards (SANS) for drinking water at least 98.333% of the time.

To the north of Lekwa, drinking water in the closely linked towns of Evander and Secunda within the Govan Mbeki Local Municipality, is acceptable. The Govan Mbeki supply comes from Rand Water, a state-owned bulk water utility, rather than from a municipal-run water treatment works. Wastewater management, however, for which the municipality is responsible, is failing in these towns, as it is in Bethal which also falls within the Govan Mbeki municipality.

Active citizen and resident of Evander, Corrie Badenhorst, led us to a non-functioning wastewater pump station in a field on the north west of town. All the sewage from its collection network flows across an open field, via a stream into the Grootspruit river. The Grootspruit runs south into the Waterval River, a tributary of the Vaal. Beyond contributing to pollution of the Vaal, the untreated sewage first flows into a wetland less than a kilometer away, which is visibly polluted. Wetlands are supposed to be protected under national environmental legislation for their ecological services (such as flood mitigation, groundwater recharge, biodiversity, carbon capture), but this pump station, which Badenhorst claims is the only one in Evander, has been dysfunctional for “about ten years.” No visible action has been taken and no-one has been prosecuted.

The Green Drop Report shows the Evander wastewater treatment plant scored just 17% for microbiological compliance, and 48% for chemical compliance, with an overall score of just 35%. An overall score of 31% or less indicates the plant is in “critical risk” and to be placed under regulatory focus.

The Govan Mbeki municipality did not respond to questions, including whether it had a single pump station within the sewerage network. If Badenhorst’s assertions are correct, the Evander wastewater treatment plant is failing despite not even receiving a large portion of the sewage within the sewerage network. Much of it is simply flowing into the environment before getting to the treatment plant.

In Bethal, southwest of Evander and within the Govan Mbeki municipality, the wastewater treatment plant was not working at all when GroundUp visited on the morning of August 18, due to loadshedding.

An employee at the plant, who is not allowed to officially speak to the media, said they have no generator and are subject to national load shedding schedules as well as additional power cuts due to municipal infrastructure failures.

He said when they do have electricity only one of four aerators work, a biofiltration unit also doesn’t work. This is largely due to cable theft, he said.

“As soon as they fix the cables, they get stolen again.”

Asked about a series of large holding ponds, he explained that when the wastewater flow contains high chemical levels, as well as blood from the abattoir, it is diverted to the ponds to settle. It is then supposed to be pumped back to the plant for treatment, but the return pump wasn’t working. Instead, the water from holding ponds flowed through a break in the lowest pond, through an informal settlement and into the wetland environment.

“It’s flowing into the stream without treatment,” he said.

The Green Drop report gave the Bethal wastewater treatment works an overall score of 36%, placing it in the ‘high risk’ category, with microbiological compliance of 0% and chemical compliance of 58%.

The cost of mismanagement

Neither Govan Mbeki nor Lekwa municipalities responded to questions about failures in sewage or drinking water provision, but financial records, reflected on Municipal Money – a web-based tool designed to inform citizens on their municipality’s financial performance using data from the National Treasury – indicate the extent of mismanagement within these institutions.

According to the data, Govan Mbeki Municipality underspent its capital budget by 54.5% in the last reported financial year (2020/21). The capital budget is used for infrastructure projects such as new water pipes or wastewater treatment plants. Equally, spending on repairs and maintenance, which would cover the preservation of sewerage and water supply networks, was a mere 2.5% of the value of the municipality’s fixed assets, when it should be 8%.

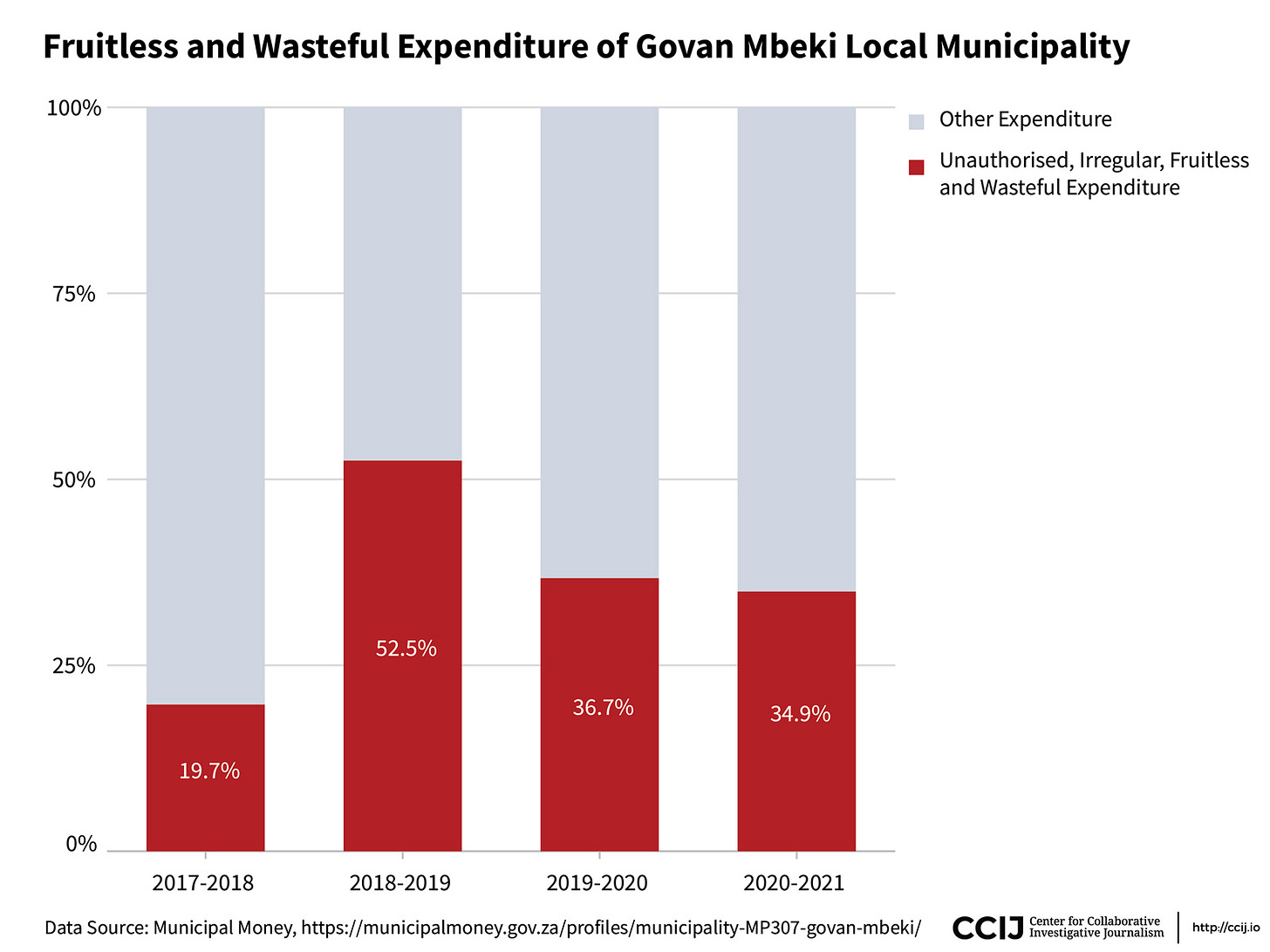

“Unauthorized, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure” comprised 34.9% of the budget in the last financial year. It was 36.7% of the 2019/20 budget and more than half – 52.5% – in the 2018/19 financial year.

While data and anecdotal evidence show Govan Mbeki municipality’s drinking water meets national standards, the Auditor-General (A-G), in its qualified report, noted 7.7 billion liters of this water was lost during the financial year “due to wastage as a result of deteriorating infrastructure.”

The municipality incurred a net loss of R608,88 million ($35.27 million) for the financial year, and liabilities exceeded assets by R195,13 million, ($11.3 million) leading the A-G to state there is “a material uncertainty” whether the municipality has the resources to continue operating.

Lekwa municipality’s financial state is possibly worse, with the A-G’s office stating the municipality was unable to provide sufficient documentation for an audit opinion to be formed. The A-G accounting officer stated in their report that if it were not for the audit of the municipality being a legislated requirement, they would “have withdrawn from the engagement in terms of the International Standards of Auditing.” In other words, if the municipality were a business, it would not be able to produce properly audited financial reports.

Damningly, the A-G found the municipal infrastructure grant, which is provided by the national government for infrastructure to service the poorest households, was “not spent for its intended purpose”.

Due to the poor reporting and financial record keeping, there is little information from the 2020/21 or 2019/20 financial years loaded onto the Municipal Money site. However, it shows “unauthorized, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure” took up 41.1% of the budget in 2019/20. The A-G notes that no reasonable steps have been taken to prevent this loss of money.

The result of this mismanagement is more than 57 million liters of untreated or partially treated sewage flowing to the Vaal River every day, just from these two municipalities. But it has an impact far beyond the immediate environment. This daily 57 million liters only comes from one corner of the vast upper Vaal catchment area, yet sewage failure is a characteristic of all the municipalities. Beyond sewage pollution, this catchment also receives agricultural runoff containing high levels of nitrates and phosphates, as well as acid mine drainage, all of which goes into the only supply of drinking water for much of Gauteng Province, as well as parts of Mpumalanga, such as Govan Mbeki municipality.

A dire warning

These areas form South Africa’s economic heartbeat, but Rand Water, the bulk water supplier for this region, did not answer questions about the impact of sewage and other pollution on their drinking water supply from the Vaal Dam. They said the questions fell under the competence of the Department of Water and Sanitation who failed to respond. However, a water quality specialist at Rand Water, who cannot be named for fear of losing his job, issued a dire warning if the matter is not addressed.

He explained that while pollution within the Vaal catchment has had serious environmental impacts over at least the last decade, it has not yet affected water purification capabilities or costs. He said this is because the microbiological component – the E.coli and related gut bacteria – does not last long outside the human gut, so it was not a factor by the time the water flowed to the Vaal Dam, and even if it was, it would be killed by chlorine.

However, the chemical component,the nitrates and phosphates, do remain. The water purification process is designed to remove these elements within a wide margin of concentration and he said we are currently “fairly far” from exceeding these margins.This is partly because the Vaal Dam is so large, which allows for sufficient dilution, and partly because a good rainfall season, such as the last two in a row, has prevented the build up of chemicals.

“The simple answer is that the cost (of water purification) is not affected, but if it gets to that point, it would be drastic,” he said.

Although this might be a decade or more away, he said he was not hopeful it would be avoided. He pointed to increased pollution from continued municipal dysfunction married with population growth, a failure to deal with acid mine drainage and agricultural runoff, combined with a few years of drought as experienced by Cape Town in 2017, as factors that could push the Vaal Dam to a point of eutrophication. This occurs when an influx of nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, stimulate algal growth to the point where oxygen is removed from the water making it incapable of supporting life. Eutrophication also leads to blooms of cyanobacteria (commonly known as blue-green algae) which produce toxins that can be fatal. Studies show that once a water body has become eutrophic, it may take a thousand years for it to recover.

The Rand Water employee said eutrophication of the Vaal Dam was “a long way off,” but warned that “if we get to that point,” there would be nowhere else to go in terms of water supply for the roughly 10 million people who rely on the dam for drinking water.

However, Anthony Turton, a Professor at the University of Free State’s Centre for Environmental Management, who is also a specialist in acid mine drainage, said there was “no question” the Vaal Dam was already moving toward a eutrophic state.

Turton cited several studies showing around 60% of large dams in South Africa had become eutrophic and said “we’ve never managed to turn it around.”

He explained that current bulk water treatment methods cannot remove the toxins produced by blooms of cyanobacteria. These toxins, he said, have been proven to injure motor neurons in the brain, impairng cognitive function. They can also cross the placenta, bioaccumulating in the fetal brain.

Turton did point out that water from a eutrophic dam can be purified to drinking water quality through charcoal activation or advanced oxidation, but said neither of these methods were currently in use.

What is clear is that while Johan Lotter and his parents continue to have to live in a fecal swamp, a national water security crisis is creeping ever closer with each kilolitre of untreated sewage that flows into the Vaal from these failing municipal systems.

This investigation was produced in collaboration with the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and OpenUp, with the support of the Open Society Foundation.

A version of this article was first published by GroundUp.

CCIJ Editorial and Design Team

Melissa Mahtani

Scott Lewis

Jillian Dudziak