Clemency Controversy Questions Corruption Commitment

Prison congestion also reportedly played a role in this year’s pardons. Malawi’s prisons operate at 149 percent capacity on average.

LILONGWE, Malawi — Not every criminal qualifies for a presidential pardon in Malawi, as outlined in Section 89(2) of the country’s constitution, writes Regina Kadzuwa.

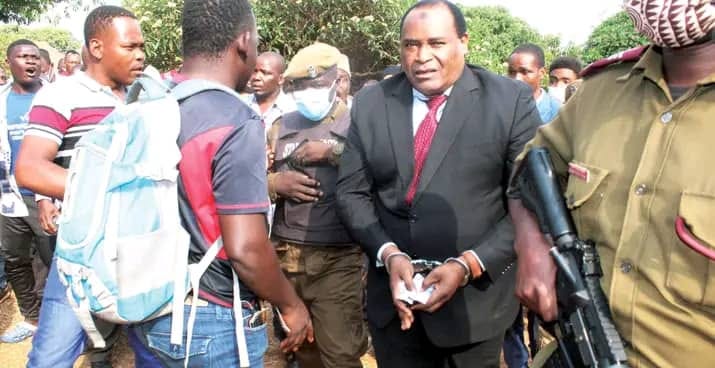

But the recent release of jailed former government minister Uladi Mussa has raised scrutiny over President Lazarus Chakwera’s use of pardons, calling into question his commitment to fighting corruption.

Mussa, the former Minister for Home Affairs and Internal Security under former President Peter Mutharika, was convicted on corruption charges in 2020 and sentenced to five years in prison.

He served over half that term before being pardoned and released on April 10 along with 47 other prisoners by President Chakwera.

While Chakwera’s office has claimed Mussa qualified for pardon by exhibiting good behavior and remorse after serving a substantial portion of his sentence, critics argue his corruption crime should exclude him from presidential clemency.

“While a pardon is an act of mercy, the release of someone convicted of a serious offense like corruption raises questions about the government’s commitment to combating corruption,” said Michael Kaiyatsa, the executive director for the Center for Human Rights and Rehabilitation, a leading rights group in Malawi.

But Frank Namangale, the public relations officer for Malawi’s Ministry of Justice, defended Mussa’s release, noting it adhered to the conditions for pardon laid out in Section 111 of the Prison Act and Section 89(2) of the constitution.

“The president relied on recommendations from a pardon committee, of which the Minister of Justice is a part,” Namangale explained.

“The complexities surrounding presidential pardons underscore the delicate balance between mercy and justice in the criminal justice system.”

According to Chimwemwe Shaba, the national public relations officer for the Malawi Prison Service, those conditions give the president authority to show mercy to convicted offenders based on age, time served, behavior, health and other factors.

Prison congestion also reportedly played a role in this year’s pardons. Malawi’s prisons operate at 149 percent capacity on average.

The 48 pardoned prisoners had all served more than half their sentences.

“This group included 37 convicted prisoners who had served half of their sentences and exhibited reformative conduct, along with four elderly individuals and seven breastfeeding mothers who were accompanied by their children to prison,” Shaba told the AfricaBrief.

Shaba added that while presidential pardons aim to give second chances, they are only granted through a careful review process focused on reformation - one that does not include perpetrators of Malawi's most serious offenses.

Whether Mussa's corruption conviction falls into that category remains hotly debated as Chakwera continues using remissions and pardons to alleviate overcrowding in correctional facilities.

But any appearances of special treatment for public officials could intensify doubts over this administration's pledges to root out graft.